Building a tool set for journalism collaborations

Introduction

You’re ready to collaborate but first you need to figure out how and where to manage the work.

While it may be both comforting and disappointing to know that no one has figured out the perfect set of tools or the perfect process by which to select the specific tools that will work best for your collaborative project, there are things we can do to make the process more manageable.

Selecting tools to manage the editorial process is no easy task, whether it’s working by yourself as a freelancer or piloting new tools for your organization. It becomes especially challenging when trying to build a tool chain that works for multiple partners that can encompass freelancers, non-news partners, and newsrooms big and small.

While it may be both comforting and disappointing to know that no one has figured out the perfect set of tools or the perfect process by which to select the specific tools that will work best for your collaborative project, there are things we can do to make the process more manageable.

Your tool set may change by the project, the partnership or the limitations of your working situation at any given time.

What follows is a guide to ensuring that basic structural needs are accounted for when working in partnership with others and a series of steps and questions you can answer with your partners to find and make use of the best tools for the work you are trying to do.

It takes time to assess, test and adopt tools, even more so when doing it across multiple partners. It is easy to get bogged down in deciding on your infrastructure. Avoid tools where the complexity of the tool itself outstrips the complexity of your project unless all partners are comfortable and well-versed with the tool and its complexity is an asset. It’s important to remember that partners should be equally able to afford and acquire the tool. Be careful to not push partners toward adopting something that’s new to their organization and that might cost them a lot of money just because it’s what your organization is most familiar with or is already using.

When working collaboratively, seek the simplest solution that is appropriate and fitting for your project.

Core Needs

The tools you use should reflect meeting a specific need for your project or situation rather than an effort to use the latest and supposed greatest of what’s available.

A collaboration’s needs can vary widely depending on the complexity, degree of integration and duration of a project or collaborative relationship. (See more about this at collaborativejournalism.org/models/)

Simple projects with a limited number of partners and a limited duration of engagement with a low level of production expected don’t require all that much infrastructure and many can get by with email, instant messaging and some shared storage and files. But as projects get larger or more complex, there are multiple needs that a project might have to account for. The following sections are organized by core needs, common needs and potential needs.

Every project needs to consider how these four needs will be accounted for from an infrastructure perspective:

- Communication Among Partners

- Documentation

- Editing/Review/Preview

- Asset Management

Communication Among Partners

Communication is the linchpin and most important factor upon which the success or failure of a collaboration often rests. Accounting for how communication will take place, by what means and what the expectations are for frequency and conduct is a critical component of collaboration

There are three primary pathways for communication:

Voice: One-to-one calls or teleconferences

Text: Email, instant messaging, group chat, text messaging

Video: Video chats

Text-based tools provide records that are easy to make available to the group at large when there is a need for everyone to access the information or be in the loop. But easy access is harder to accomplish with voice and video. If you find yourself often using teleconferences or video chats to brief partners, consider what note-taking or recording steps are necessary to make sure that absent partners are fully included. (Note, this is also important for equitable accessibility considerations.)

- What is the likely volume of communication to manage this project?

- What are the expectations around frequency and participation?

- Responding to emails in a timely manner is a different thing than expecting quick responses to instant messaging

- What kinds of communication will require a record so that everyone can stay in the loop?

- How many people will need to be included in every communication versus those who can get by just fine with fewer interactions?

Documentation

For everyone involved to be fully included and empowered to participate, they must all have access to the essential information about the collaboration: the goals, the timelines, procedures, commitments and deliverables. This requires a level of documentation that matches the complexity of your project. Perhaps this is a simple Google Doc that has been shared with everyone or perhaps you need a living set of documents that are a running resource connecting everyone with the information they require to remain fully engaged and effective in their work.

- What information must be accessible to all teams at all times?

- Is the documentation going to be static or a constantly updated repository of information about the project and its status?

Editing/Review/Preview

Regardless of the nature of a collaboration, at some point, partners will likely need access to the content itself either for collaborative creation, editing, reviewing, or previewing it as part of the process.

This means deciding how content will be shared and what permissions might be necessary to grant to different users. The most permissible version of thinking here, and likely the most common, is that most people can see and work on most things, with less need for tight control beyond whatever expectations have already been set by leadership or mutual agreement.

One of the primary challenges in this need space is version control. If content is being moved around via file-sending through email or shared storage where files are fixed at a point in time with limited edit history, then it can be easy for multiple parties to be working on different versions at the same time, making a final merge of content difficult or time-consuming. If content is moving around this way, file-naming conventions become particularly important.

The scenario becoming more common and reducing the headaches in this space is a system that uses a browser or app-based version of the content that multiple parties can collaborate through with fewer opportunities for overwrites or lost changes. A challenge to look out for here is permissions and ensuring that everyone has access and the potential for additional cost as tools that charge by the seat may become cost-prohibitive when you need a large number of people to have access.

As you’re planning your project, establish how content needs to be available to partners and at what point in the process.

Collaborative creation/editing: Content needs to be available to all relevant parties as early in the process as possible along with a clear idea of how changes will be made. If this is by moving files around via email or sharing services, establish naming conventions and expectations around comments in the files so that changes are clear.

Review/Preview: Partners need access to finalized content to plan around running that content, to offer feedback or to otherwise be aware of what partners are producing. This can be accomplished through a variety of means. The challenge here is ensuring that any updates, corrections, etc. also propagate to all partners who had access to the original version.

- Who needs access to content and at what point, if any?

- Do we need one version of the content that everyone has access to at all times?

- Who is responsible for backups?

Asset Management

This refers to both internal planning assets like notes, timetables, story budgets, contact sheets, logos, etc. and the publishable rich assets that partners will need access to for whatever platforms and versions of content they may be publishing.

This often happens via email, but it’s wise to maintain assets in a central repository to which all relevant parties have access. This helps ensure version control and consistency across partners and platforms.

Consider what assets you will likely have as part of your project and create a clear structure for managing and making them accessible.

Common Asset List:

- Photos

- Graphics/Illustrations

- Video

- Audio

- Logos

- Embed Codes for interactives/visualizations

Additional considerations: File naming conventions for photos, audio and video clips are important as it is all too easy for people to dump a lot of things into a folder without proper metadata or names. Sorting IMG0001 through IMG9000 is a task that no one wants to do after the fact. Establish a baseline of expectations here to keep this a manageable situation.

- What assets will likely be a part of this project?

- Are there so many that we need to establish conventions and expectations?

- Do we need multiple versions of a single asset to account for different publishing needs

- Who is responsible for keeping a backup copy so that should someone’s computer bite the dust or the web service be offline, the assets are not lost or completely inaccessible?

Common Needs

More tightly integrated, long-term or complex projects frequently need to account for these needs:

- Task Management

- Schedule Management

Task Management

This topic has an entire selection of books that could be assigned reading, but we’ll limit this discussion to the simplest set of considerations to make so that work can get done and that everyone involved knows who’s responsible for what, what its relative status is, the expected outcome and the timeline.

This can be as simple or as complicated as you like, everything from a shared spreadsheet to using tools that are dedicated to task management. Your needs here will be dependent on how complicated your project is. It’s advisable to not make the tools more complicated than the project itself. If you and your partners are well versed in a specific task management system, then it’s more likely to help than hinder, but if you and you’re partners are not on fairly common ground here, it’s easy to sink a lot of time into something that may be more robust than the work requires. Let the complexity of your project drive the complexity of tools in this instance. If you can make do with a spreadsheet that tracks the work to be done, that is fantastic. If you truly need a complex system for a complex project, then this particular need may require some planning and discussion among partners. In later sections, we discuss what things to think about when considering and testing tools.

- How much detail does your task management require?

- Tasks for a whole project?

- Tasks for a specific story?

- Tasks for different aspects of the project?

Schedule Management

Similar to task management, perhaps this is a text file or spreadsheet with milestones and shared timelines or perhaps it’s a more complex Gantt chart or calendaring system. If you need infrastructure to support schedule management, its complexity should match the complexity of your project.

- What kinds of dates, times and timelines are you needing to keep track of?

- Deadlines for copy

- Deadlines for tasks and benchmarks

- Expected run dates

- Events that are part of coverage (something you will report on)

- Events that are part of the project (something you are hosting)

- Internal meetings and check-ins

Possible Needs

These needs are less common but should be assessed as to whether they are relevant for the project you are working on.

- Joint Marketing Management

- Audience Engagement

- Metrics Tracking

- Impact Tracking

- Analytics

Joint Marketing Management

Whether your partners would simply like to share language for social media posts to avoid duplicating efforts or your project has a sophisticated, coordinated roll out, some process by which to coordinate the marketing of the project can be useful.

- What aspects of marketing would be useful for collaboration?

- Social media posts

- Newsletter language

- Banners or graphical ads on websites

- Promo audio

- Social video

- What/If any rollout/marketing scheduling should be shared or collaborative?

Audience Engagement

With collaborative projects that have a high level of audience engagement, it’s important to be clear by what means that engagement is taking place and how access and sharing will happen among the partners.

- Is it a form that everyone embeds and then has access to all the responses? Or just those of their audiences?

- Is it a system or service that facilitates audience engagement?

- Is it a tool that fewer than all partners need access to?

Tracking success metrics

Where are you recording what success metrics are being tracked, and how will you note status and benchmarks throughout the project and after its conclusion?

Measuring Impact

If you’ve outlined how you will gauge the impact of your project, do those metrics require some form of documentation, logging or tracking that will need to be in an accessible form?

Analytics

Do you need a system for sharing analytics that are relevant or useful to partners?

Common Scenarios

There are six primary models of collaboration based on Sarah Stonbely’s examination of 25 collaborative projects.

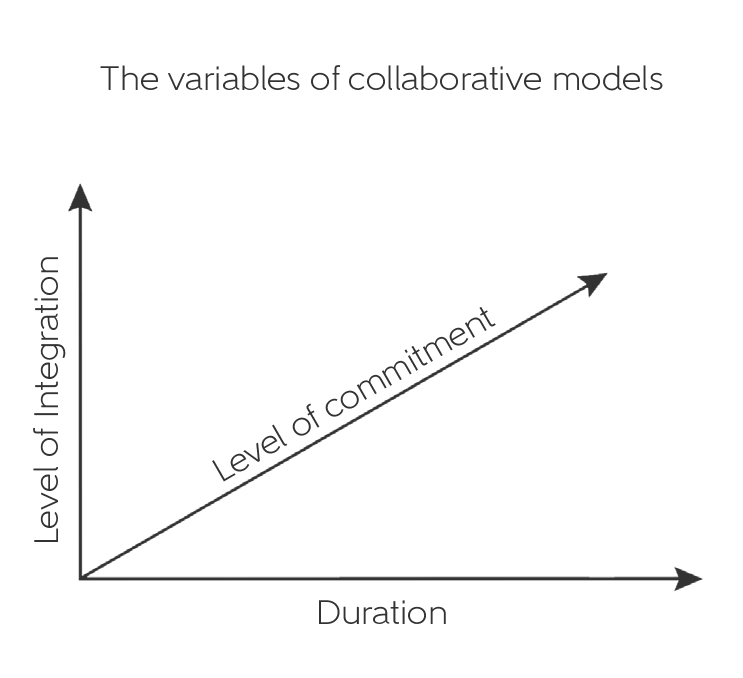

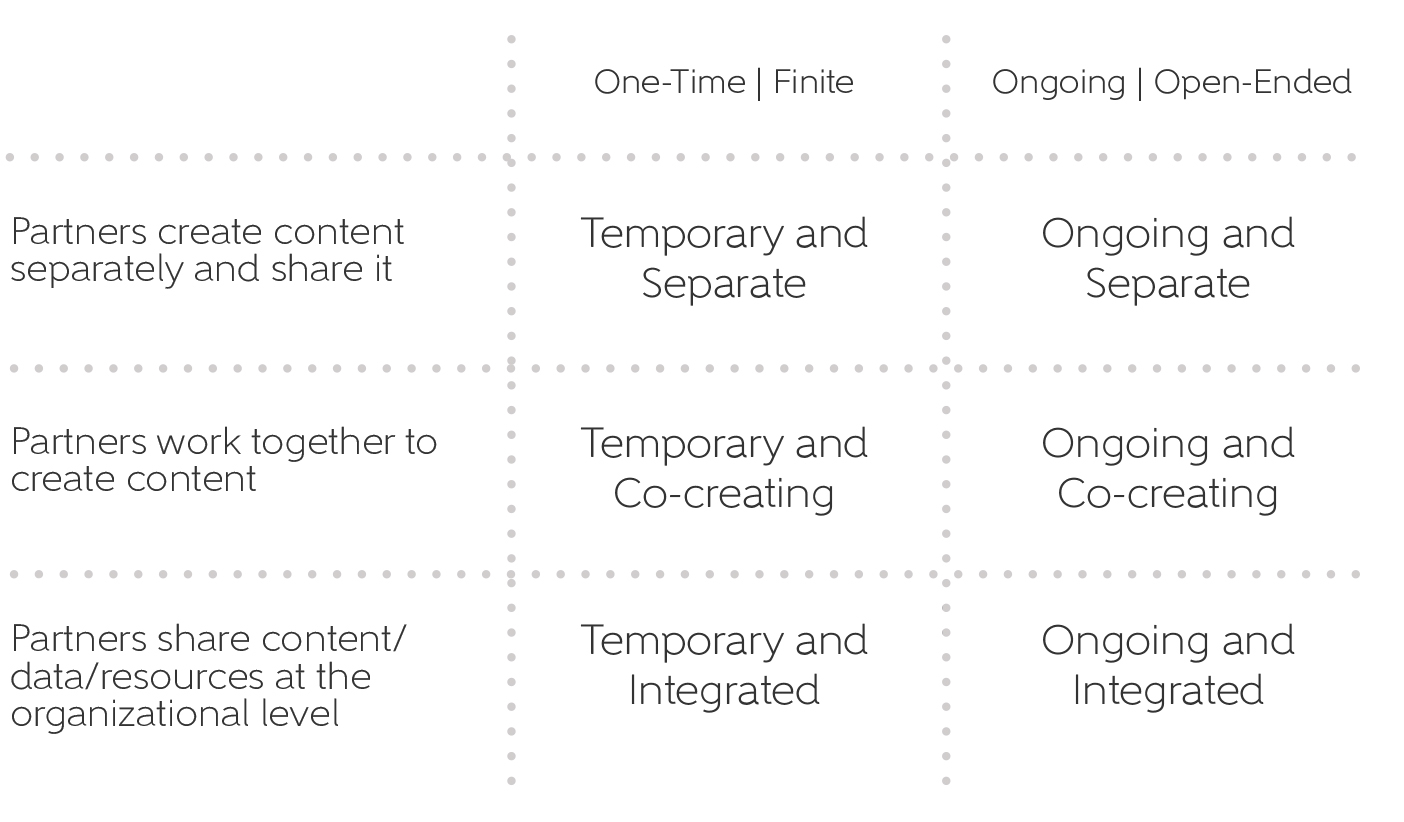

“We have identified two of what we think are the most important elements by which collaborations are organized: duration of time, and degree of integration among partner organizations. As both of these increase, the level of commitment required to make the collaboration work also increases. Using these two variables, we have identified six different models of collaborative journalism.”

Those same elements: duration and level of integration are effective metrics to guide how complex your tool chain for collaboration must be and how much time it’s worth investing into choosing and implementing tools.

Shorter Duration

Least Integrated

Duration of Collaboration

Level of Integration

Ongoing Duration

Deeply Integrated

Temporary & Separate

Mid-Range Projects

Ongoing & Integrated Projects

Choosing and assessing tools

Choosing Tools

There is no one system for collaboration and in the majority of cases, collaborative projects are assembling chains of tools that largely meet their needs as they collaborate. Considering which tools may be appropriate for a project depends on a variety of factors.

If your collaboration has an independent or appointed facilitator, you might ask questions about how they work.

- What existing tools do partners already have in common?

- If you can prevent the friction of introducing unnecessary work by using things that participants are already using and familiar with, then you can devote that time and energy to the work at hand.

- What is the capacity for on-boarding and supporting all the users that will need to be on the tool?

- If the project requires tools that are new to some partners, then supporting those users as they get up to speed on how the tool works and how it fits into the workflow is part of the consideration.

- Are there tools that only certain participants will need access to?

- You may have some instances where only certain partners or participants will need access to a tool that facilitates their particular section of work. If that’s the case, seek means by which the work they are doing can still be shared with others so that everyone is in the loop.

- How much work is it going to take to use a tool compared to how complicated the task is?

- Many things can be accomplished with a phone call or email and a text doc or spreadsheet. Let the complexity of your project determine the complexity of the tools you use, not the other way around.

Assessing Tools

To decide whether a potential tool is the right fit for your partners and your project, it’s important to think through how the tool is likely to be used.

Users

- Types of users and number

- Are you supporting different users that fulfill different roles within the project? If so, what does that mean for all the different needs you need to account for?

- If you need to support a larger number of users, be sure to budget appropriately if the tool charges per seat.

- Support for multiple languages

- If working on multi-language projects, will the tool or workflow allow for organizing versions of the content in multiple languages?

- If working with multiple languages across teams, does the UI support languages of the participants?

- Permissions management

For the most part and for most projects, a fairly open approach to permissions works for permissions management. Allowing most people to do most things is a reasonable plan. However, if you are managing a complex project with a variety of stakeholders, permissions management becomes more of a concern.

- What kind of participants will be involved in the project?

- Do you need to maintain different viewing/editing permissions for these users?

Platforms

While there is no one specific platform to recommend for better apps, it’s important to remember that partners may span the gamut of technology that’s available to them. Some newsrooms have new machines, access to different phone devices while others are working with years-old computers running older operating systems or are located in areas with poor connectivity. Account for the most accessible denominator when choosing tools. Browser-based technologies over specific OS downloads have a broader range of access. Keep in mind that you or your partners may run into challenges with using certain platforms if you are part of a large institution with strict requirements around security. For example, partners affiliated with universities often have problems with getting approval from IT to use some platforms or around using the free version of certain platforms.

Free vs. Buy vs. Build

Free

- Lifespan: May be limited by how well supported the free version is.

- Limited Features: Limitations (seats, functionality, exportability) may be imposed.

- Limited Support: Customer support may not be available beyond existing documentation.

Paid

- Scale: May be able to better accommodate a project that continues and evolves.

- Cost: If the cost is per seat, this may lead to people not having access in order to contain costs. Be aware of pricing structure when planning budgets and considering tools.

- Support: Will likely have a higher level of support for your users.

Build

Building your technology should be a last resort if there is truly nothing out there that will work and if you have the means and ability to build and support the work and ongoing support and maintenance.

- Initial Cost: The upfront cost of building a tool is often substantial.

- Ongoing Cost: Because you’ve built it, you are responsible for all ongoing costs around hosting, third party services or premium APIs.

- Maintenance: Maintenance can be particularly daunting if what you’ve built is so bespoke that you run into trouble with funding and hiring people who can maintain it. If you’ve built it internally, this is a long term staffing consideration. If you’ve hired someone externally to build it, if they should close up shop or become unavailable, will you be stuck with something that no one in your organization can manage?

- Supporting all users: Responsibility for all on-boarding and support ticketing will be part of the lifespan of the tool.

Friction of Adoption vs. Potential Benefit

How much work is it going to take to use this tool compared to how complicated the tasks are?

- More users = more work to onboard and support

- The more complex the technology, the more carefully to consider whether it’s a good fit

Lifespan

Tools that are likely to be around for a while:

- Some version of it is paid

- Has some form of funding

- Backed by an institution or company

- Are built with more modern frameworks/technologies

Control

Using someone else’s tool or platform always means ceding some level of control.

- Can you save/export a version of your work off platform?

- Do you have access to any kind of analytics?

Third Parties

When working with companies that create, manage or support technologies that we need to use for journalism, doing due diligence on their policies, practices and terms of use are an important part of evaluating tools for potential use.

- What are the terms of agreement from the company?

- Is there anything that conflicts or jeopardizes being able to do journalism using that platform?

- Does the company have backdoors into the software that is accessible to law enforcement or government agencies without notice to you?

- Are there automated processes within the tool or platform that could potentially cut off access to your content? (e.g. an algorithm interpreting a news story about terrorism as being promotion of terrorism and locking your account)

- If the company is subpoenaed for your account information or content, do they have a track record of standing for the user’s rights or handing over the requested items?

- Is there any evidence that a company responds to requests for data and information without informing the user about it?

- Has the company ever had a significant data breach?

Other considerations

- Duration of use (one-off vs. long term)

- Has someone written about using the tool or platform?

- Shared documentation of things individuals and teams have tried

- Avoid tool/tech envy. Use things that meet a need for your project, not because it’s new or trendy.

Pitching and adopting technology

Adopting Technology

Support users

- Examples of usage

- Documentation

- Clear Workflow

Part of your collaboration documentation should include which tools are being used in addition to what changes have been made to either tools or workflow.

Pitching Technology

When bringing a group together and assembling the tool chain to be used by everyone, decisions have to be made. When recommending tools, there are details that everyone should be able to consider.

- Be clear on the value received for the cost

- Be realistic about the risks and opportunities and err on reducing risk

About this Guide

The Center for Cooperative Media

The mission of the Center for Cooperative Media is to grow and strengthen local journalism, and in doing so, serve New Jersey citizens. The Center does that through the use of partnerships, collaborations, training, product development, research and communication. It works with more than 270 partners throughout the Garden State as part of a network known as the NJ News Commons, which is its flagship project.

The network includes hyperlocal digital publishers, public media, newspapers, television outlets, radio stations, multimedia news organizations and independent journalists. The Center is also a national leader in the study of collaborative journalism. It believes that collaboration is a key component of the future success of local news organizations and healthy news ecosystems.

The Center is a grant-funded organization based at Montclair State University’s School of Communication and Media. The Center is supported with funding from Montclair State University, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, Democracy Fund, the New Jersey Local News Lab (a partnership of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, Democracy Fund, and Community Foundation of New Jersey), and the Abrams Foundation.

For more information, visit CenterforCooperativeMedia.org.

About this guide

This report is part of a series of five collaborative journalism guides produced in 2020 by the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University, thanks to generous support from Rita Allen Foundation.

The Rita Allen Foundation invests in transformative ideas in their earliest stages to leverage their growth and promote breakthrough solutions to significant problems.

The guides were also produced in partnership with Heather Bryant, who agreed to update her Collaborative Journalism Workbook for inclusion as one of the series’ six guides.

To see the guides online, visit collaborativejournalismhandbook.org.

To learn more about collaborative journalism in general, visit collaborativejournalism.org.

About the Author

Heather Bryant is the founder and director of Project Facet, an open source infrastructure project that supports newsroom collaboration with tools to manage the logistics of creating, editing and distributing collaborative content, managing projects, facilitating collaborative relationships and sharing the best practices of collaborative journalism. She published the Collaborative Journalism Workbook and works with the Center for Cooperative Media to build resources for collaboration. Bryant researches and writes about the intersection of class, poverty, technology and journalism ethics.